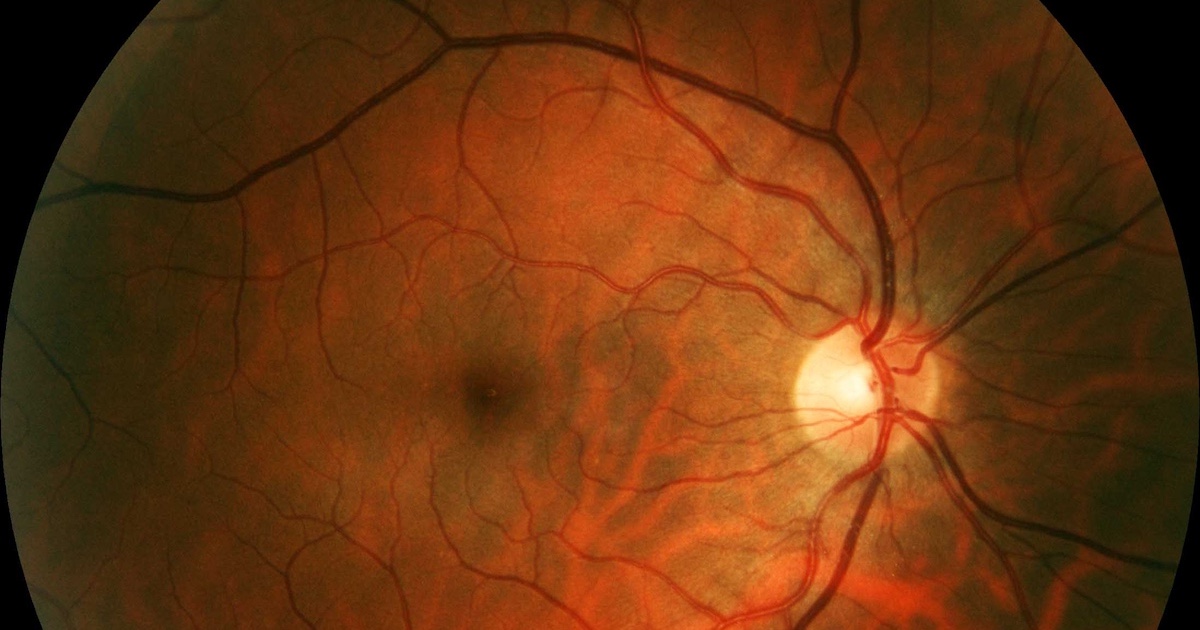

Dr. Erik Langhoff

Photo courtesy of Dr. Erik Langhoff

According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the traditional paradigm of medical device regulation was not designed for adaptive artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies. As a result, changes to AI- and ML-driven devices may need premarket review.

In January, the FDA published the Draft Guidance: Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Device Software Functions: Lifecycle Management and Marketing Submission Recommendations, which proposes lifecycle considerations and specific recommendations to support marketing submissions for AI-enabled medical devices.

In April, bipartisan senators introduced the Health Tech Investment Act (S. 1399), which would establish a Medicare reimbursement pathway for FDA-cleared medical devices that utilize AI and machine learning.

Dr. Erik Langhoff, chief medical officer and consultant for the Bronx Regional Health Information Organization, sat down with MobiHealthNews to discuss the current state of the FDA certification process for AI devices, liability issues and how consumers can be assured that AI tools are safe and effective.

MobiHealthNews: How would you assess the current state of the FDA certification process for AI devices?

Dr. Erik Langhoff: The AI certification process will change a lot in the next couple of years, because of the whole demand for AI apps in healthcare.

So, if you look at the FDA report, by July 2025, the FDA has certified more than 1,200 AI and care applications. That is a lot.

Seventy-seven percent of those are radiology applications, 9% are cardiology, 4% are in neurology, and the other clinical areas take off the rest.

Just as a comparison, the FDA approved through the past 25 years between 18 to about 60 drugs per year, and that was all the chemicals and the biologicals. This process is very different.

So, the question is, how is it going to be in the future? Because AI in medicine is just in its first steps. There is going to be a lot more development, and there is also going to be a lot more pressure for the FDA to keep up in the certification process even through a faster track for medical devices.

I think the FDA is doing a great job, no doubt about that. But there is also a question: Is the FDA capable of keeping at scale? Is there enough staffing, enough people with insight into AI that can really accomplish such a big task?

So, one of the things that comes into consideration is that if you look at the regular drug approval process, the history has been that it has been a very narrow and deep approval process that can take maybe 10 years, or even longer, from the first discovery to maybe final approval.

The cost of some drugs before they got to the market, including obtaining FDA approval, could be hundreds of millions of dollars for some of the newer modulating agents or cancer treatment agents.

Now, if we look at the AI process, we are not talking about 10-years approval cost. We are talking about a much shorter turnaround that will be necessary and relevant if they are not becoming outdated.

So, the thought is, how are we going to make sure that we as consumers know that we have a transparent process and we have a thorough process that really makes sure that we get products that will satisfy us and also be safe for us?

MHN: You said that when it comes to AI guidelines, you are concerned about how we make sure that the products we use are certified. Could you elaborate on that?

Langhoff: I cannot help thinking about the common Heinz ketchup bottle. In 1870, Heinz was the first company to put in some guidelines/product labels for what is really inside the bottle.

They did that as a marketing tool, because they were the first and then all the others could not really show what happened, but the idea was good.

And I cannot help thinking that we have something similar for AI health products or AI vendors that can give us the same insight, because AI is not like drug development. In drug development, there's a long process of testing those drugs in clinical trials, maybe in animal studies.

I do not think this will be the certification process for AI products. But yeah, as a consumer, you would like to have some general description of what is in the box, what is under the hood.

MHN: It sounds like what you are saying is that you believe there needs to be new guidelines, a new set of standards. Is that correct?

Langhoff: I am talking as a consumer because I do not have the specific background to say these should be the guidelines.

Some information should be made available to the consumer. What is the general purpose for this? What are the outcomes? What are possible limitations? What kind of data has been used to develop this? What has validation cost? Is there time of expiration, and what is the ongoing maintenance of the data?

I think these are some very basic questions that at least I as a consumer would like to know and get a little more feel for in terms of what is under the hood.

MHN: You mentioned protections for bias in AI functions or outcomes within the community, such as lemon laws or medical liability for developers regarding adverse medical results. What did you mean by that?

Langhoff: What I mean by that is, as an AI developer, you take on a degree of responsibility for function and outcomes.

If you use AI apps in healthcare, it becomes a device the same way as an FDA-cleared device in medicine.

And the question is then, how are you covered if you get some biased or negative outcomes, or if the device is not working according to the developer’s intent? For other products, there are laws.

If you buy a car that does not seem to work as it should, we have a lemon law. Again, if an interventional device results in adverse outcomes, there is some kind of liability for the company.

It is not clear to me that we really have that kind of setup for the future in AI healthcare development. How do we make sure that we can develop products that are trusted among the consumers?

MHN: How can we ensure that AI devices are trained on enough data on rare conditions to guarantee consumer safety for all?

Langhoff: This is something about labeling, but also something about proceeding with caution as just mentioned.

Google’s deep learning system for differential diagnosis of skin diseases was recently published in Nature Medicine. The paper showed that by using their AI diagnostics for skin disorders, they could make a diagnosis for 60 different kinds of skin disorders, and that was an impressive outcome.

But in the aftermath concerns have been raised. What was really done?

The study used actual pictures of skin disorders to train their deep learning system. Is that really trained on everybody so that you get a recent reference, representation or skin colors? And it was not.

Of the thousands of skin condition pictures used for training, only 3.5% came from patients with very, very dark skin. It's called Fitzpatrick skin type five and six.

So, that brings up the question, and I heard that before at another conference, when a woman stood out in the middle of the meeting and said, "Listen, I have a very rare disorder. How do I know that that robot knows about me?" I think that is really the key issue. It struck me that that person stood up and was so frank and said, "I am special."

We need to have a very thoughtful pathway going forward of how we make sure that everybody feels that they have trust.